|

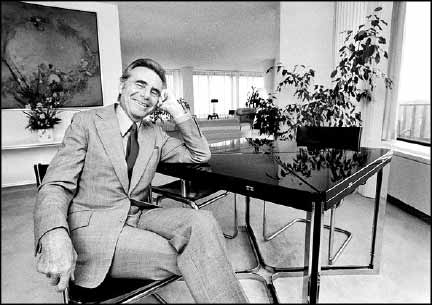

Nicolas M. Salgo, 90, an immigrant who became a millionaire financier and developer and whose properties once included the Watergate commercial and residential complex, died Feb. 26 at the home of a friend in Bal Harbour, Fla. He had Shy-Drager syndrome, a neurological disorder.

The Hungarian-born Mr. Salgo received his first burst of attention in the 1950s as a top aide to William Zeckendorf, who turned the New York firm Webb & Knapp into a major developer of properties, including the United Nations. Known as one of Zeckendorf's "no men," Mr. Salgo often reined in some of his boss's proposals. "If you are not willing to stick your neck out and take responsibility," he said at the time, "what else are you but a glorified errand boy?" Soon he was focusing on his own investment and development projects. He was involved in the conception and construction of the Watergate complex, built in the mid-1960s on an undeveloped site in the Foggy Bottom neighborhood. He represented an Italian real estate firm, partly owned by the Vatican, that hoped to profit from plans to build a highway through the land, and then to create distinctive "curvilinear" structures to reflect the swerve of the freeway. Mr. Salgo and a partner bought the property in 1977 for $49 million. He was chairman of the Watergate Cos. until 1983, when his long campaign to serve as ambassador to Hungary was fulfilled. He spent three years in Budapest, followed by many years as a State Department special negotiator on property issues. One of his most prominent roles came in negotiations with the Soviets about the fate of the U.S. Embassy building in Moscow, which had been compromised by electronic bugging devices. He also traveled to other former Soviet satellite countries to develop sites for new U.S. embassies. He was a recipient in 1992 of the National Intelligence Distinguished Service Medal for his work. "I felt that Hungary owes much to Wallenberg, and since official action on such a delicate matter sometimes is very late to come," he told the Associated Press, "I figured that a private initiative would facilitate building bridges." He was born Miklos Salgo in Budapest in 1914. It was years before he saw his father, a lawyer who had been captured by the Russians during World War I and spent years in a Siberian prisoner-of-war camp. As a young man, Mr. Salgo considered studying engineering but turned to law as a practical matter. He told the New York Times in 1957: "I was able to cut classes, do my studying at home and take the exams and still hold down a job, whereas I would have had to spend my time in class and the lab if I was going to pass anything in engineering." Of his own accord in 1987, he funded the construction in Budapest of a bronze-and-granite memorial to Raoul Wallenberg, the Swedish diplomat who is credited with saving Hungarian Jews during World War II and who disappeared during the Soviet seizure of the city. Mr. Salgo commissioned Hungarian sculptor Imre Varga to design the statue, which replaced an earlier one that vanished from a square in central Budapest. |

|